Voyage of the White Widow is undeniably funny and I think most audience members left

happy (I know I did, although a bit embarrassed for other reasons). My Barbarian's targets were wide ranging--colonialism, heteronormativity, pop culture, musical theater, narrative, global warming, the list goes on. The performers, too, seemed to enjoy themselves in a "I-can't-believe-we-get-paid-for-this" way as they danced in undies and played with puppets. Though My Barbarian managed to get in a number of good barbs, it's hard to take away a strong message from the spectacle other than a handful of art history in-jokes and some general zaniness. The performance, though immensely enjoyable, didn't seem to have any real depth. I'm unsure whether there's actually a problem with that or not.

happy (I know I did, although a bit embarrassed for other reasons). My Barbarian's targets were wide ranging--colonialism, heteronormativity, pop culture, musical theater, narrative, global warming, the list goes on. The performers, too, seemed to enjoy themselves in a "I-can't-believe-we-get-paid-for-this" way as they danced in undies and played with puppets. Though My Barbarian managed to get in a number of good barbs, it's hard to take away a strong message from the spectacle other than a handful of art history in-jokes and some general zaniness. The performance, though immensely enjoyable, didn't seem to have any real depth. I'm unsure whether there's actually a problem with that or not.Haircuts by Children seems like it would also serve up some zaniness, but though images of clown-like haircuts and true green locks may flash through your minds, the event was actually

much more sober. The children--actually Middle School aged so a bit older than one might expect--are given training before they cut and at least at this performance, took the job quite seriously. The role change subverts power in a thoroughly untraditional way: by offering a service, the children manage to gain control of the adult whose hair they cut. As unlicensed and unexperienced barbers, the children must garner the trust of the adults and ultimately put them in a submissive position. The children are not expecting any tips from the free haircuts, nor are they protecting a reputation or career, so their ability to render any adult ridiculous is just a snip away. The project creates an interesting web of power and exposes some of its mechanisms.

much more sober. The children--actually Middle School aged so a bit older than one might expect--are given training before they cut and at least at this performance, took the job quite seriously. The role change subverts power in a thoroughly untraditional way: by offering a service, the children manage to gain control of the adult whose hair they cut. As unlicensed and unexperienced barbers, the children must garner the trust of the adults and ultimately put them in a submissive position. The children are not expecting any tips from the free haircuts, nor are they protecting a reputation or career, so their ability to render any adult ridiculous is just a snip away. The project creates an interesting web of power and exposes some of its mechanisms.

This weekend I attended Garnerville's

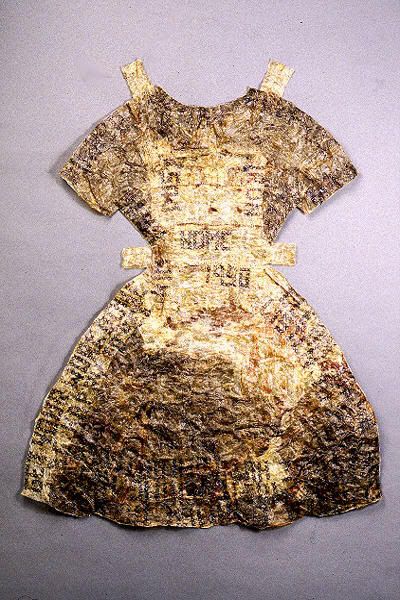

This weekend I attended Garnerville's  Regardless, I did manage to find an artist whose work I really enjoy, Pat Hickman. A former professor and head of Fiber Arts program at University of Hawaii, Hickman's work is reminiscent of Kiki Smith's in material and occasionally style, but very distinct in tone and themes. Hickman's most striking work is created from organic materials, most commonly pig's intestines. Although the material she uses is one that would evoke disgust from most viewers, she transforms the material into a beautiful, thin golden skin-like material, such as in the piece to the right titled "One Size Fits All." The piece takes insides and turns them into outsides--clothes. But only superficially, as the piece itself admits by mimicking a paperdoll dress.

Regardless, I did manage to find an artist whose work I really enjoy, Pat Hickman. A former professor and head of Fiber Arts program at University of Hawaii, Hickman's work is reminiscent of Kiki Smith's in material and occasionally style, but very distinct in tone and themes. Hickman's most striking work is created from organic materials, most commonly pig's intestines. Although the material she uses is one that would evoke disgust from most viewers, she transforms the material into a beautiful, thin golden skin-like material, such as in the piece to the right titled "One Size Fits All." The piece takes insides and turns them into outsides--clothes. But only superficially, as the piece itself admits by mimicking a paperdoll dress. Another piece, "The Beginning of the Beginning," pictured on the left, uses notes and thread to create a tapestry of what looks like, upon close inspection, a series of small paper notes and to do lists. The threads cross off the items on the notes; the tasks are completed and subsumed into the larger work.

Another piece, "The Beginning of the Beginning," pictured on the left, uses notes and thread to create a tapestry of what looks like, upon close inspection, a series of small paper notes and to do lists. The threads cross off the items on the notes; the tasks are completed and subsumed into the larger work.